I'm taking part in another blog hop. This one starts today and lasts one week. It promotes Mocha Memoirs Press' new holiday releases as well as some of its backlist.

There's a list of participating blogs below as well as a Rafflecopter whose prizes include ebooks, gift cards, and swag.

But first, my own blog-hop post on the most important holiday in ancient Mesopotamia . . . one that celebrated barley and continues to be celebrated by millions of people to this day.

✥✥✥✥✥

The Akītu festival of Mesopotamia

|

| Barley, Hordeum vulgare vulgare [public domain] |

Barley, a wild grass, was harvested in the Fertile Crescent to make beer perhaps 11,000 years ago. People then discovered how to make bread. Over time, people began planting barley in fields to have a more reliable source. Once they had control over the growth of barley, they selected for several traits that made the barley plant produce more barley. Eventually, most people of the Fertile Crescent settled down in villages near their barley fields.

In Mesopotamia, barley beer and barley bread were daily staples. The earliest written records that mention the barley (akītu) festival date to the mid-2000s B.C.E. The festival celebrated the sowing of summer crops and the harvest of winter crops. However, only a small percentage of the documents created before then survive and have been translated. The akītu festival could have been millennia old by then.

The barley festival outshone all the other festivals and marked the New Year. The festival was celebrated around the spring equinox and was called akītu (in Sumerian and Akkadian) or reš šattim (in late Akkadian dialects).

Some Sumerian cities, such as Ur and Uruk, celebrated akītu at both the spring equinox and the fall equinox. Over time, the festival evolved, taking on additional meanings and adding new rituals.

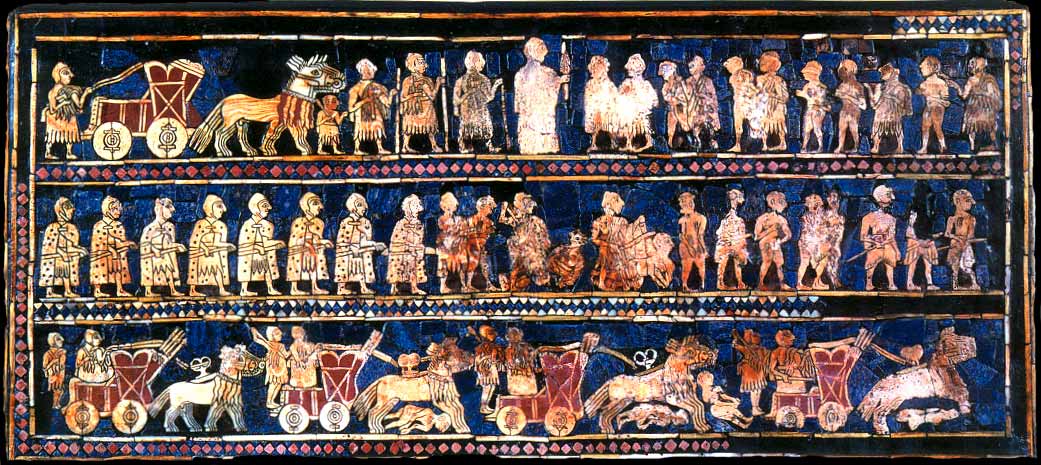

By the time of the Babylonians and the Assyrians, the spring and fall akītus, respectively, had become a complex and lavish 12-day extravaganza. Among many, many other events, the akītu now included feasts; dances; singing (both solemn hymns and bawdy songs); performances that included recitation of a creation epic and re-enactments of myths; religious rites; sacrifices; the humbling and penitence of the naked king followed by his crowning or re-crowning; and a procession in which the statue of the main god [Tammuz (or later Marduk) for the Babylonians and Ashur for the Assyrians] left his temple to face danger each year and conquer it, returning in a triumphant parade. Meanwhile, statues of lesser gods processed in new clothes to the temple of the main god to honor him.

|

| An aurochs, one of many beautiful reliefs in glazed brick that once made the Ishtar Gate (constructed about 575 B.C.E.) in Babylon one of the Seven Wonders of the World. During akītu, statues of deities were paraded through this gate and down a long avenue decorated with glazed bricks to the temple of Marduk. [Credit: Josep Renalias, used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license] |

The Persians either adopted akītu from the Babylonians or enhanced their own existing spring festival with elements of akītu, such as the ritual "sacred marriage" between the king and a goddess (represented by either a priestess or a statue of the goddess).

This Persian New Year festival later also integrated aspects of Zoroastrianism. It still exists under a couple dozen names (including Newruz, NuRoz, Noruz, and Nowruz) and is celebrated in many countries as well as by the Parsi of India, some ethnic groups in China, and members of the Bahá'í faith. The god(s) honored by the festival, of course, have changed over the centuries, and in some places it is now a secular festival.

|

| Novruz feast in Azerbaijan [Credit: Азербайджан-е-Джануби; used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 Internationallicense] |

|

| Shofar made from a ram's horn. The shofar is blown before and during Rosh Hashanah, which today lasts one or two days and focuses more on penitence than on singing and performances. [Credit: Olve Utne; used under the Creative CommonsAttribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license.] |

In the first to third centuries C.E., several peoples of northern Mesopotamia and nearby areas converted to Christianity. Since then, these groups have been subject to persecution and even many massacres. Over the centuries, many fled to other countries and now spread around the world. Massacres continue to occur in the 21st century. The most recent one took place in 2014 in northern Iraq, when terrorists belonging to Daesh attacked towns of Christianized Mesopotamians.

Other names, such as Chaldeans, Syriacs, and Arameans, reflect differences in believed ancestral place of origin, the variant of Christianity they belong to, the language or dialect they speak, and other factors. The names and origins of the "Assyrians" are controversial, even among the groups themselves. If you have friends who trace their ancestry back to Mesopotamia, don't automatically assume they consider themselves Assyrians; they may, for example, be proud Chaldeans.

Despite the cultural differences that accrued over hundreds of years of Assyrian diaspora, despite the need for the Assyrians to sometimes hide their identity, the akītu survived. Many Assyrians today celebrate the spring akītu on April 1. It has developed several other names including Resha d-Sheta (which is pronounced much like its ancient Akkadian name, reš šattim), Kha b' Nisan, and Ha b' Nison.

Wild barley still grows across a wide swath of northern Africa, southern Europe, and Asia. Genetic studies show that, like the akītu festival that celebrates it, cultivated barley has changed but remains recognizably like its ancestors of 5,000 years ago.

✥✥✥✥✥

a Rafflecopter giveaway

✥✥✥✥✥

The stories and books that Mocha Memoirs Press is promoting are:

“It’s Christmas, Cupid!” by Dréa Riley

“Under theMistletoe” by Siobhan Kinkade

“Holly and Ivy” by Selah Janel

Mistletoe Dreams bundle containing three stories:

—"A Trick of Frost" by Dréa Riley and RaeLynn Blue

—"Naughty Klauses" by Dréa Riley

—"Winter’s Guard" by Laurel Cremant

✥✥✥✥✥

Other blogs taking part and offering holiday-themed posts—maybe a favorite recipe, a top-ten list, a flash story, or an essay about a holiday or a holiday symbol—are listed below. Click on each name to go to the linked post.